You know that one slow-motion scene in every tennis film where the crowd’s head whips back and forth as they follow the tennis ball? Now imagine if every time the cameras (assuming the audience is also watching on those giant screens) switched sides, the players’ positions on the court flipped too.

That’s what happens when you break the 180-degree rule: you mess with the established orientation of the characters in relation to the audience and confuse them.

Let’s back up a little bit…

What Is the 180-Degree Rule (+ How it Works)

The 180-degree rule is a cinematography norm followed during the filmmaking process.

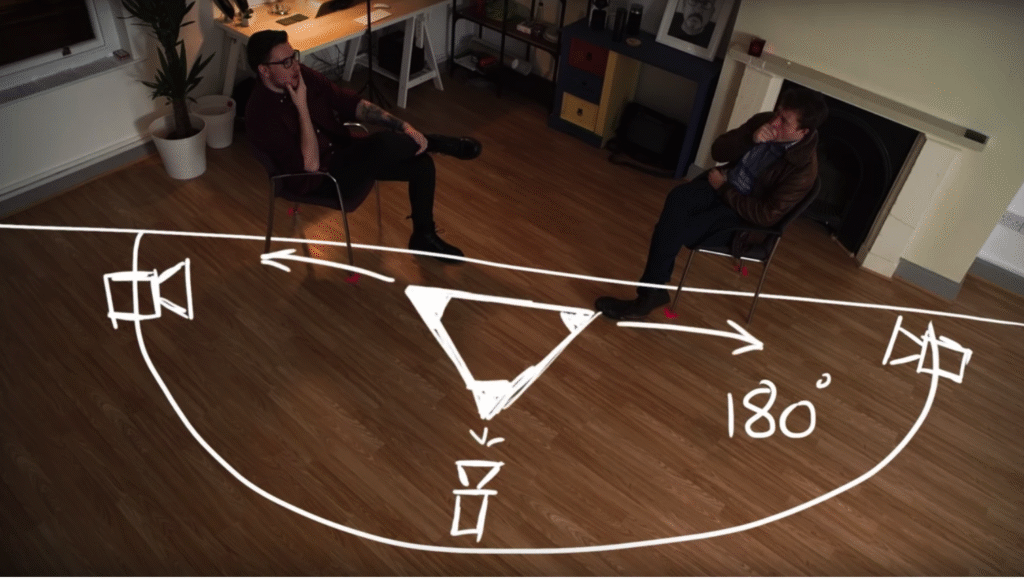

The rule assumes an axis between character A and character B, or between character A and an object. The cinematographer keeps the camera on one side of this axis throughout the scene. If it crosses the axis. Ensuring the camera remains on one side of the axis makes the scene easy to follow.

In the image above, the axis runs through the character on the left (Character A) and the one on the right (Character B). The three camera illustrations denote various positions the cinematographer can place them. All three positions are on one side of the axis.

If Character A and Character B are talking, and the camera is positioned on one side of the 180-degree line, with Character A facing right and Character B facing left, this orientation (them looking at each other and talking) will be maintained.

If the camera is placed on the other side of this axis, say to the right of Character B in the same scene with the same characters in subsequent camera setups, then both Character A and Character B would be looking in the same direction, i.e., to the right. Not ideal if you want to show them talking to each other.

A study suggests that viewers can detect violations of the 180-degree rule. Even if they don’t know the concept by name, they experience confusion and feel disoriented when the rule is broken.

Why Is the 180-Degree Rule Important?

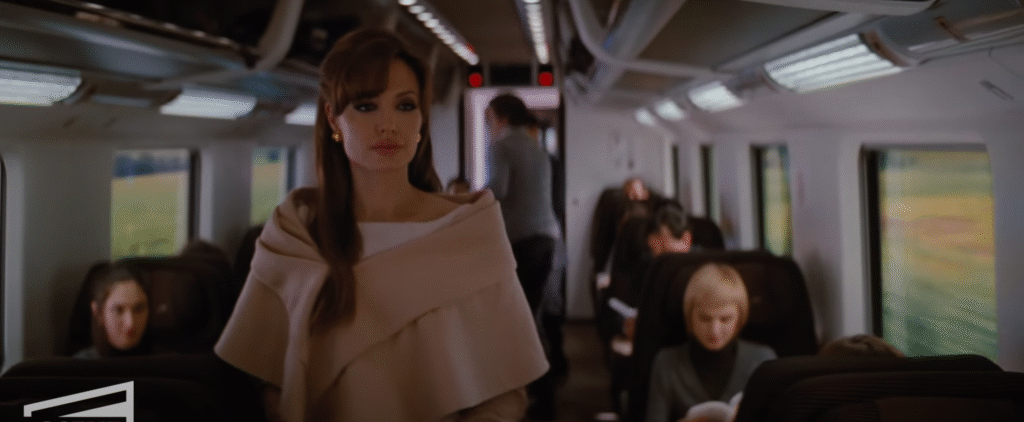

Let’s break it down with this scene from The Tourist (2010), starting at 0:39, when Elise (Angelina Jolie) sits down across from Frank (Johnny Depp):

Imagine the window as the axis running from Angelina Jolie (Character A) to Johnny Depp (Character B). They face each other as they talk. The orientation of the characters is consistent throughout, and the conversation is easy to follow, despite the numerous angles. Narrative immersion is intact. That’s because the filmmakers are adhering to the 180-degree rule effectively.

Practical Application of the 180-Degree Rule on Film Sets

On paper, the 180-degree rule seems simple. Draw a line between your two subjects, and don’t let the cameras cross it. But on set? It’s a whole different ball game (yes, we are sticking to tennis wordplay here).

Once the axis is decided, every camera setup is designed to stay on one side of it. Here’s what that entails:

Scene blocking

Scene blocking refers to the process of deciding:

- Which character will stand where during a scene

- How the characters will move from this initial position to other positions as the scene progresses

“Blocking” here essentially means deciding the positions and movements of characters during the scene and how they interact with the environment.

The director works with the cinematographer to determine these positions and movements (sometimes marked with gaffer tape on set). Once the scene is blocked, i.e., the positions and movements of the characters are determined, the cinematographer and director will decide on the camera setups to establish where the 180-degree axis lies, ensuring that the cameras do not cross the axis during the scene.

Therefore, scene blocking should be done keeping in mind the 180-degree axis and placement of cameras.

Let’s go back to the train scene from The Tourist (2010). At 0:28-0:30, Angelina Jolie stops. Scene blocking determines where she stops, and the camera is placed accordingly. The camera is placed at just the right distance, not so far that her expression is not visible, and not so close that only her face is visible.

Coverage

Coverage means shooting a scene from multiple angles and shot sizes, allowing the editor to select the best options. For a two-person conversation, coverage might include:

- A wide shot of both characters

- A close-up of each person

- Over-the-shoulder shots

If a shot crosses the axis unintentionally, it becomes unusable, so the editor will have fewer shots to pick from.

What Happens When the 180-Degree Rule Is Broken?

That depends. If you break it accidentally, you are likely to be flipping the audience’s visual understanding.

Left becomes right.

A chase scene feels thrilling because you won’t be able to figure out who is chasing whom.

A conversation feels like no one wants to meet each other’s eye.

In short, continuity breaks, thus leaving the viewer disoriented.

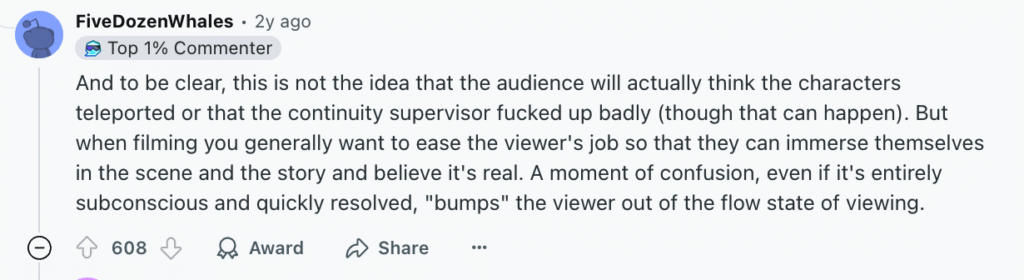

So, directors follow the 180-degree rule because viewers are supposedly less intelligent? No! It’s because breaking the rule can affect the viewing experience. This Reddit comment explains the effect of breaking the rule quite well:

But if it does none of the above, and it’s necessary to establish emotion or stay true to the story? Directors happily break the rule.

Academy Award winner Walter Scott Murch, known for his film editing and sound design in The English Patient (1996) and editing for The Godfather Part III (1990), succinctly explains this in his book ‘In the Blink of an Eye: A Perspective on Film Editing.’ Here’s an excerpt:

If the emotion is right and the story is advanced in a unique, interesting way, in the right rhythm, the audience will tend to be unaware of (or unconcerned about) editorial problems with lower-order items like eye-trace, stage-line, spatial continuity, etc.

Just like writers bend grammar to evoke emotion, filmmakers also bend this rule. When done intentionally, the rule break can make the scene much more intriguing.

Breaking the 180-Degree Rule to Create Tension, Chaos, or Surprise

Here are three reasons why a director will intentionally break the 180-degree rule:

To Disorient the Viewer

This scene in Jaws (1975) is an excellent example of breaking this rule for a surprise effect. Steven Spielberg wanted you to feel the visual distress that the character faces (when the shark surfaces, causing the character to be stunned), so he broke the 180-degree rule.

When the shark surfaces and Brody steps back in surprise (0:15 to 0:21), you will experience some disorientation to mirror his surprise of spotting the shark so close to him. That’s the point at which the 180-degree axis is crossed, as you can tell with this eyeline shifting to the right (it was to the left before this point).

To mark a shift in power

However, the 180-degree rule break is not just for horror films or jump scares. In this scene from The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers (2002), the 180-degree rule is broken. The axis is crossed to visualize Gollum’s inner shift, starting from 0:23. The camera flips sides to show his conversation with Smeagol, his “good half” and viewers can easily recognize which version of Gollum is on screen.

To shake up a scene

In Breathless (1960), Jean-Luc Godard breaks the 180-degree rule in this car chase scene when the camera flips sides with jump cuts (1:52-2:07). The character’s position is reversed as a result. It’s jarring. The goal was to disrupt the predictable nature of a car chase scene.

Do All Scenes Require the Usage of the 180-Degree Rule?

No, only the scenes that require specific character orientation need the 180-degree rule. Many scenes do not rely on spatial clarity, and breaking the 180-degree rule in such scenes doesn’t ruin the audience’s viewing experience. For example:

- Shots where a character is talking straight into the camera (an eye-level shot or neutral shot) don’t rely on directions, so there’s no axis to break.

- Since the 180-degree rule requires two subjects, single-subject scenes won’t have an axis, and thus, the rule cannot be broken.

- Montages, since in those scenes, the rhythm and emotion prevail over any spatial orientation.

180-degree Rule: Our Final Take

The 180-degree rule is one of the first things you learn on a film set or in film school, especially if you are training to become a cinematographer. It exists to establish clarity, but as we saw above, there are ways to circumvent it or disregard it. If broken well, it can shift the viewer’s perception in a way that enhances their watching experience, rather than detracting from it.

Ever felt disoriented while watching a scene? Now you know why.

I want reading and I think this website got some genuinely useful stuff on it! .